MWS | Writing Styles

Welcome to the OCWC's MWS Writing Styles sub-module! Here, you will be able to learn about some of the higher-order concerns involved in writing in a second or foreign language.

What is a "Writing Style"?

A Writing Style is a way of writing that is comprised of tone and the level of directness, the order of presenting ideas or argumentation, the level of descriptive or emotional language, and the cultural expectations that shape the writer's purpose and goals.

While a great many writing errors do derive from grammatical differences between languages, as we have seen in the Language and Grammar Modules so far, many errors actually originate in cultural communication and writing style based distinctions between languages. This is called Contrastive Rhetoric (Kaplan, 1966).

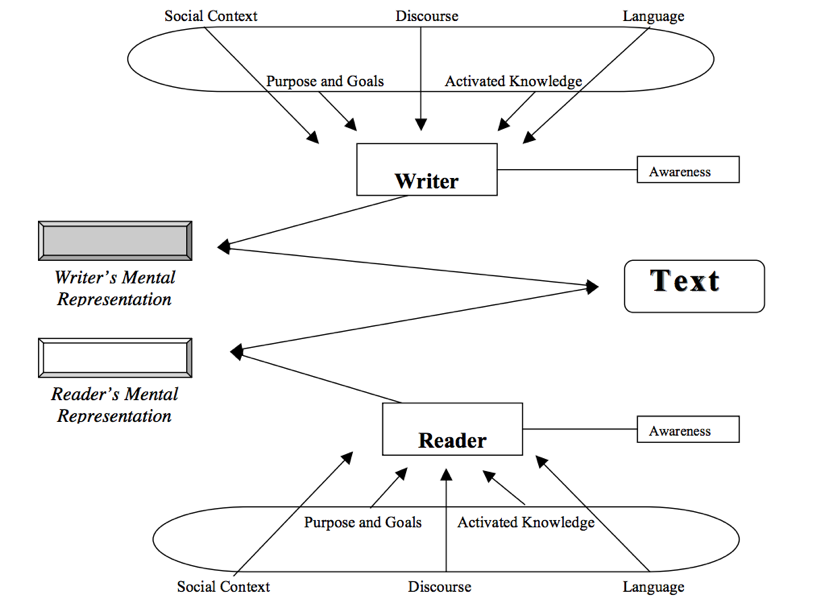

Because writing is a socially informed process, a writer must consider several elements when choosing a written manner of sharing their ideas with an audience; these include:

- The writer's social context, purpose and goals, activated knowledge, language, and how these construct into the writer's discourse awareness and expectations

- The text as a medium between the writer's mental representation and the reader's mental representation of the ideas

- The reader's social context, purpose and goals, activated knowledge, language and how these shape the reader's discourse awareness and expectations

This can be seen graphically in the flowchart from Flower et al. (as cited in Krampetz, 2005) following.

Figure 1. Model of Discourse Construction adapted from Flower et al. (as cited in Krampetz, 2005).

A Writing Style is, therefore, a textual discourse medium that is selected based on the writer's purpose and goals in addressing the reader (i.e., what mental representation of the text is desired from the reader), which is informed by the writer's social context, language use, and activated knowledge.

Translanguaging Between Writing Styles

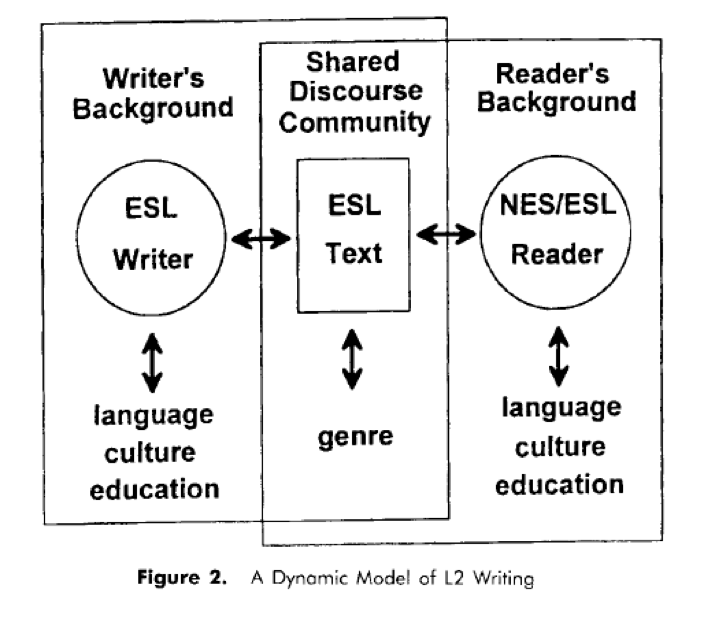

When we account for multilingualism in this bilateral, two-way process of writing as an interactive social practice, the task of creating a written work becomes even more involved. Referring back to Contrastive Rhetoric, because multilingual writers have to navigate two sets of the elements of discourse construction, or to translanguage between their L1 and L2, a multilingual writer needs to think not only of whether their writing is grammatically correct and communicates their meaning clearly, but if that intended meaning is perceptible and in a format that can be comprehended by a reader whose L1 context and expectations of written work may be very different.

Several key principles shape Contrastive Rhetoric that can assist multilingual writers in addressing this potential breakdown in communication and fully translanguaging between writing in their native language and academic English writing.

- The writer's 'context': the cultural and linguistic expectations and communicative purpose and goals of written language in the writer's L1

- The text created: the use of the L2 language to represent the writer's meaning and participate in the shared academic discourse community

- The reader's 'context': the cultural and linguistic expectations of a native English reader and how they perceive the writer's purpose and goals

Figure 2. A Dynamic Model of L2 Writing (Matsuda, 1997) for explicating the bilateral, multidirectional nature of writing as a social process.

This model asks multilingual writers (and their readers) to consider how social context, language, purpose and goals, and resulting discourse shape a written work. To do this, it is important to understand some of the basic categories of writing style distinctions between linguistic cultures.

- Social Context: Indirect or Direct

- Discourse: Linear, Anecdote-Embedded, Circular, Digressive, or Freely Arranged

- Language: Elaborate or Understated

- Purpose and Goals: Collectivist or Individualist

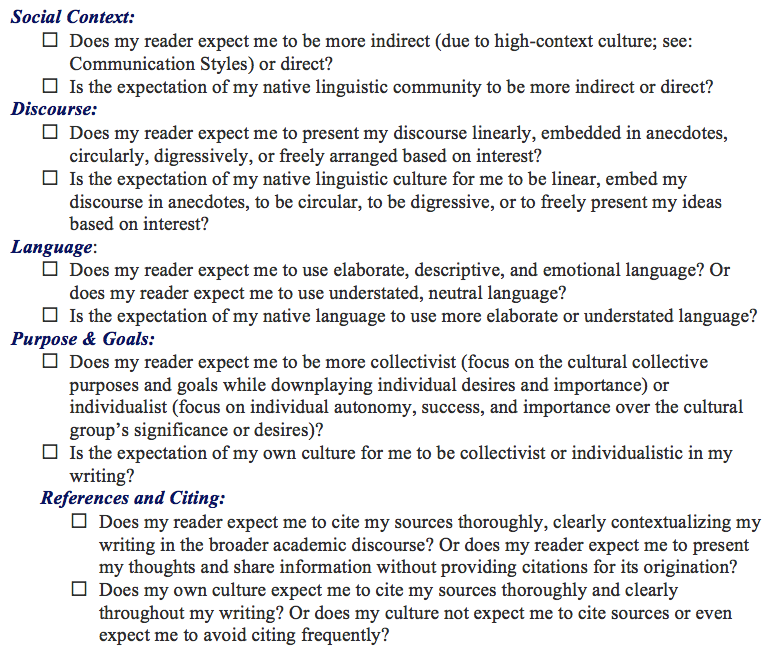

A Checklist for Multilingual Writers' Academic Writing Style

Therefore, a short checklist can be generated to assist multilingual writers in expecting, explaining, and exemplifying how to address higher-order concerns in their academic English writing:

After answering these questions, multilingual writers can identify where there are large expectation differences in discourse construction in their L1 and academic English. By expecting these differences and explaining how they create different writing styles, multilingual writers can exemplify their meaning more clearly by understanding what is expected of them. Through understanding the function of the written form expected of them in writing academic English texts, multilingual writers will be able to translanguage more successfully

Writing Style Comparisons

In the following pages, you will find access to specific comparisons between many TCSPP multilingual writer's L1 writing styles and academic written English. Each language comparison will provide students with the following information, specific to their linguistic background:

- an overview of how discourse construction expectations differ between their L1 and English written social context, discourse, language, and purpose and goals,

- potential places where written communication breakdowns might occur; and

- writer-specific recommendation checklists for producing texts that align to academic English expectations in writing and overcoming the most common higher-order writing translanguaging errors.

If your native language is not available, please either check back with us or send the OCWC Writing & ESL Specialist, Gabrielle Valentic ([email protected]), an email requesting resources for your linguistic background.